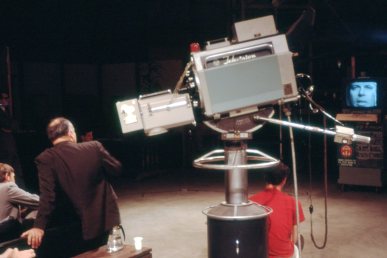

No, this is not the “prayer” photo that one might expect in a collection of six decades of pictures I’ve taken since childhood. One would look for a bowed head, folded hands, and/or sacred space of some sort. But a vintage TV camera? What kind of Lenten reflection is this?

This was the scene in a Georgia television studio in 1968 when Episcopal priest Malcolm Boyd watched the playback of an interview in which he talke d about his then-recent book of conversational and controversial prayers Are You Running with Me, Jesus? Other topics included his nightclub appearances (where he read his prayers before an admiring audience), his participation in the civil rights movement, and the state of the Church in the turbulent ’60s.

d about his then-recent book of conversational and controversial prayers Are You Running with Me, Jesus? Other topics included his nightclub appearances (where he read his prayers before an admiring audience), his participation in the civil rights movement, and the state of the Church in the turbulent ’60s.

I happened by that day, watched the interview, and took some slides.

The book of prayers came out in 1965, and I somehow missed it. (It probably wasn’t embraced by the religion department at the college where I began my preparation for the ministry.) But when I ran across a recording of Boyd reading some of those prayers, a Columbia Records release that included jazz guitarist Charlie Byrd accompanying Boyd and musically interpreting the prayers, I was intrigued and inspired.

It wasn’t just the conversational style, but the honest, sometimes disquieting, content of the prayers that appealed to me. I grew up with memorized prayers, as many of us do, and spoke to God more casually as I grew up. But my prayers were “safe,” guarded, and repetitious. Boyd’s broke new ground for me.

Perhaps his approach is best summarized in his book’s introduction:

“Prayer could no longer be offered to God up there but to God here; prayer had to be natural and real, not phony or contrived; it was not about other things (as rationalized fantasy or escape) but these things, however unattractive, jarring, or even socially outcast they might be.”

A few titles of Malcolm Boyd’s prayers (the prayers’ first lines really) make clear his focus: “She doesn’t feel like an animal, Jesus, even though she’s being treated like one” (about a migrant farm worker); “Blacks and Whites make me angry, Lord;” “The kids are smiling, Jesus, on the tenement stoop;” “This young girl got pregnant, Lord, and she isn’t married.” Race, sexuality, the worlds of commerce and show business, urban life, and meditations on the cross…all give rise to prayers of empathy, questioning, and love, love profound and prophetic.

“This is a homosexual bar, Jesus.” “I’m nowhere, Lord, and I couldn’t care less.” “I’m having a ball, and I just want to thank you, Jesus.”

And this one, so appropriate to the photo above. “I’m with you in a television studio, Jesus…Cameramen, prop men, men on lights, script girls, the director…a publicity woman–they’re all hard at work…Do all these people know you’re here too, Lord?” [Yes, it was the 1960s, and even Boyd hadn’t learned inclusive, non-sexist language yet.]

I’ll leave Boyd’s biography to your internet search. It’s enough to say here that even today, some fifty years after its publication, this book of prayers can teach us to pray more thoughtfully, more honestly, and more faithfully, keeping always in mind that we are not alone. We are in community, one that includes a very broad and even global neighborhood. We are always among and hopefully present with sisters and brothers who daily encounter both hurt and reasons for celebration.

And on every path Jesus is running with us.

February 19, 2016 at 2:37 pm

I love this. I don’t remember his name, but I’d love to read those prayers.

February 19, 2016 at 3:49 pm

Oh, you young people…!

I’ll share the book with you, and make an MP3 of the LPs, too.